We use mathematics to study ecology and evolution at the population level. The main focus so far has been evolutionary rescue, where a population is rescued from extinction by sufficiently rapid evolution. An emerging focus is the intersection of ancestral recombination graphs (ARGs) and spatial population genetics, specifically using ARGs to infer how alleles, individuals, and populations have moved across the landscape to get to where they are today. One of the great things about theory is that we get to work on many interesting topics, which have included mutualism, infectious disease, cancer, speciation, sex chromosomes, metabolic scaling theory, and non-genetic inheritance. For a list of papers see publications.

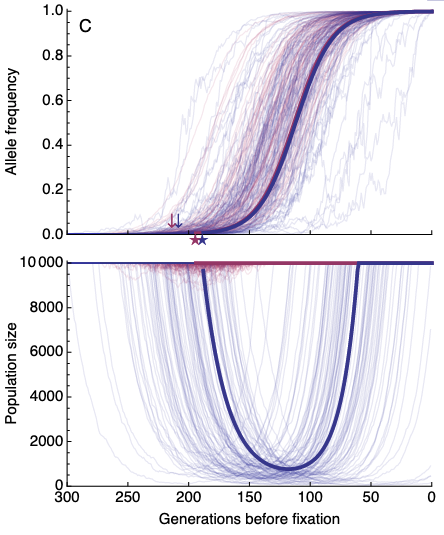

Rapid evolution can sometimes rescue populations from extinction. This process is especially important in the context of human disturbance and climate change (where we want rescue to happen) and the evolution of drug resistance (where we don't want rescue to happen). Our work has so far focused on three main areas of evolutionary rescue: 1) interactions between individuals (Osmond & de Mazancourt 2013, Osmond, Otto, Klausmeier 2018, Henriques & Osmond 2020), 2) evolutionary tipping points (Osmond & Klausmeier 2018, Klausmeier et al 2020), and 3) genetic architecture/signatures (Osmond, Otto, Martin 2020, Osmond & Coop 2020).

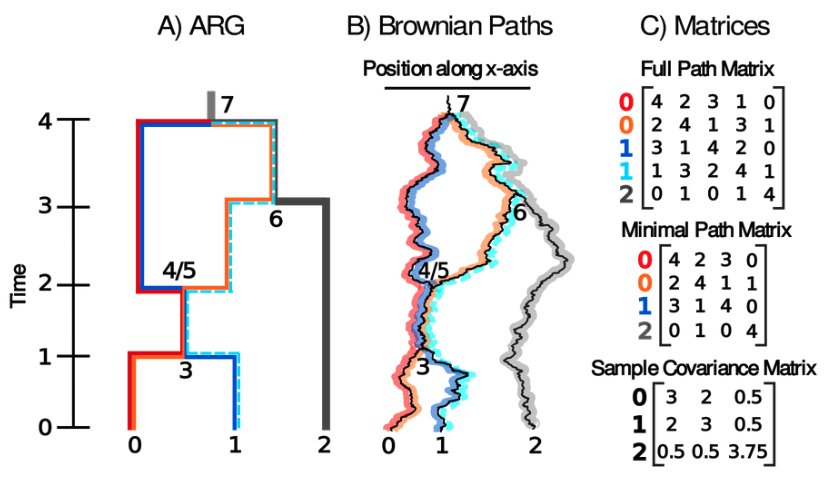

We are now able to infer the ultimate description of genetic relatedness between a set of samples — the ancestral recombination graph (ARG). An exciting new research direction is then to build methods that extract biological information from these ARGs. We've been doing just this to infer dispersal rates and locate genetic ancestors. The first method models movement down many local trees independently (Osmond & Coop 2021) while the second models movement down the full ARG in one go (Deraje et al 2024). We've developed software to apply to the former method to more species (spacetrees), including: humans, kelp, and crows.